“What’s the difference between a viola and a trampoline?”: A brief history of the viola and its ridicule

Reformatted an essay for a class I did last year. The prompt? "Write an essay on absolutely anything you want"

“Viola”

What kind of feelings does this word elicit? Search for it on Google. Did you mean Voilà? Or were you looking for the Academy Award-winning actress Viola Davis?

If you were one of the few looking for the instrument, you’d be in the minority. After all, there are probably more attractive instruments to be looking for, say, the violin or the cello. But why is it like this? Why is the viola, the middle child of the String family, so underrated and clowned upon? It’s an interesting and complex answer- one that requires us to take a trip back in time.

The birth of the Viola

As is the case with the violin and cello, there isn’t a definite time when the viola was created, but we can safely say that it originated in 16th-century Northern Italy. Consorts (ensembles made up of similar instruments) were a vital part of instrumental music of the Renaissance period. The viola covered the middle range while the violin and cello took the high and low registers, respectively.

A middle register is nice to have. But do you really need it?

In the transition from the Baroque to the Classical period, audiences wanted flashy works with plenty of virtuosity, probably to distract them from the fact that they were living in a world without social media. A popular form of music in the Baroque period was the trio sonata, which didn’t even need the viola. Solo music for the viola? Forget it. The viola was not seen as an attractive instrument by any means. Not only was it (and still is) disproportionate and weak in resonance, but it also attracted an unsavory type of musician, as is aptly summed up by the Baroque composer and flutist Johann Quantz:

“The viola is commonly regarded as of little importance in the musical establishment.

The reason may well be that it is often played by persons who are either still

beginners in the ensemble or have no particular gifts with which to distinguish

themselves on the violin, or that the instrument yields all too few advantages to its

players, so that able people are not easily persuaded to take it up.”1

Despite this rather cruel assessment of the instrument and its players, the king of the Baroque himself, J.S. Bach, dedicated the sixth Brandenburg concerto to not one viola, but TWO!

We don’t know why he did this, but this choice was certainly an unusual one, as is noted by music historian Michael Marissen:

“Bach’s treatment of the instruments in the Sixth Brandenburg Concerto is significant:

the violas and cello press forward with virtuoso solo parts, while the gambas amble

along with easy ripieno parts. In other words, as a formal correlative to his reversal of

the conventional thematic characteristics of ritornellos and solos, Bach also reverses

the conventional functions of the instruments.”

Even with this very cool move by Bach, the jury was still out on whether or not the viola should be a thing. Sure, it was a good way to fill out the middle of the harmony and beef up the strings. But as an instrument worthy of love and juicy solos?

You’re probably wondering, “But why? Why did composers shun the viola?”

The answer probably lies in the physical build of the viola. In the Baroque period, composers often had two different viola parts: an alto viola and a tenor viola. These parts were meant for two different types of violas- the “Alto Viola” and the “Viola Tenore” (as found in Sébastien de Brossard’s 1701 Dictionnaire de musique)2

While the tenor violas were far more resonant, many of them were considered to be “so large as to be almost unplayable of the arm”3

Take a look at this beautiful 1690 Viola Tenore by Antonio Stradivarius

Wouldn’t it be a dream to play on?

Not if you are vertically challenged.

The back length on this is a whopping 48 cm- or 18.9 inches in freedom units. You’d probably only find this comfortable to play if you were Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

As is expected with an instrument this size, we know from the historical instrument specialist Stewart Pollens “[T]he tenor viola was generally played in low positions that did not make extensive use of the neck heel for orientating the hand.”4 That’s fancy talk for “easy-peasy”.

Well, how did it change?

As with a lot of things in the classical period, things got sleeker. The fingerboard got longer and slimmer, allowing for ease of shifting and the ability to play in higher registers.5 The viola itself got put on the chopping block. Quite literally. Many of the tenor violas were cut down, allowing for greater technical capabilities as well as a boost in the popularity of smaller violas. The bow also evolved- while the shorter, more convex Baroque bow was ideal for the rhythms of dance music, the classical bow became longer, straighter, and heavier- allowing for “increased tonal volume, cantabile, and a wider dynamic range.6

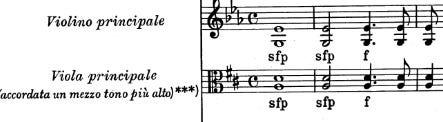

Thus, the viola was able to (kind of) step out of the shadows and into the limelight (sort of). Just look at Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola! Both parts are technically and musically demanding- one doesn’t dominate the other. Mozart even goes so far as to ask the violist to tune their instrument up a semitone for extra brightness and resonance from the open strings!

I think one of the greatest things about the classical period is that we see the viola start to really shine in the realm of chamber music. Again, we look to Mozart (thank you, Mozart!) and his six magnificent viola quintets. My favorite example within these quintets is the “Andante” from Mozart’s String Quintet, K. 515, where the viola soars over the other four instruments, often replying to the first violin melody and showing off its lyrical chops.

Some nice and not-so-nice remarks…

We have all this proof that composers of the classical period loved the viola- Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert all played the instrument. So, who did the hate come from? I struggled to find any early remarks on the viola other than from our Baroque flutist friend Johann Quantz. However, as orchestras expanded and writing became more complex, the demand for the viola also grew. It is at this point that one of the main aspects of the viola joke first appears:

1) the (lack of) ability of the viola player. Hector Berlioz had this to say about violists:

“Viola players were always taken from among the refuse of violinists. When a musician found himself incapable of creditably filling the place of violinist, he took refuge among the violas. Hence it arose, that the viola performers knew neither how to play the violin nor the viola. It must even be admitted, that at the present time, this prejudice against the viola part is not altogether destroyed; and that there are still, in the best orchestras, many viola players who are not more proficient on that instrument than on the violin.”

He did make up for it by expressing his appreciation for the instrument:

“Of all the instruments in the orchestra, the one whose excellent qualities have been longest misappreciated, is the viola. It is no less agile than the violin, the sound of its strings is peculiarly telling, its upper notes are distinguished by their mournfully passionate accent, and its quality of tone altogether, of a profound melancholy, differs from that of other instruments played with a bow.”

Our favourite unproblematic composer, Richard Wagner, had something a little less kind to say in 1869:

“The viola is commonly (with rare exceptions) played by infirm violinists, or by decrepit players of wind instruments who happen to have been acquainted with a string instrument once upon a time.”

(this could totally be made up- though it has been used in many an article)

What a nasty guy- I sure wouldn’t want to be his friend!

The “Why’s” again

Considering all the reasons I have talked about, it seems only natural that the viola would receive so much ridicule. How could it not, when:

It didn’t have the natural resonance and projection of the violin and cello due to its proportions

Violists most often started on the violin and were therefore seen as second-rate violinists ( yikes, I started on violin! )

The “middle” parts usually given to the viola were generally less technically demanding than those of other instruments, and technical difficulty = clout apparently.

With the emergence of works tailored for the viola in the 20th century, a new breed of violists appeared, like William Primrose and Lionel Tertis. These weren’t the violists who were just lousy violinists. No- these violists treated the viola as an instrument worth pursuing, and I believe the classical music world is all the better for it.

I’d like to say that the viola ridicule is no more, but that would be a big fat lie (at this point, it’s more of a tradition that has stuck amongst musicians).

Yes- It’s true that most school/youth orchestras are lacking in violists and will resort to recruiting violinists. I was once put in the 3rd violin/viola section, where I struggled with alto clef just for the sake of providing support for the one (1) violist in the youth orchestra.

But if you take a look around, you’ll notice more and more violists who are finding ways to get that unique, oh-so-smoky-and-delicious tone out of the instrument. * You’ll also find violists who make up some of the most well-respected, creative, and musical minds in the classical music world. And you might even meet a violist out in the wild and find that they aren’t as scary/disgusting/smelly/weird as you may have once thought!

*Side note: You know how literally every instrumentalist will be like “Oh, I love my instrument because it’s the closest to human voice.” Just stop bro, we get it, you play the cello. You wanna hear the real closest instrument to the human voice? The Viola! Take a random person off the street and ask them to sing. Their voice will likely crack and be a little hoarse. That’s the real human voice! The Viola is a raw, unfiltered, un-autotuned human voice. It can have beautiful, full moments as well as imperfect sensitivity. But also, stop saying that x instrument is the closest to the human voice. Literally go listen to an actual human singer. Touch grass. Seek help.

So, I have just one question for you:

Q: What’s the difference between a viola and a trampoline?

A: You take your shoes off to jump on a trampoline.

References:

Berlioz, Hector. “BERLIOZ’ TREATISE UPON MODERN INSTRUMENTATION AND ORCHESTRATION.” Chapter. In A Treatise upon Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration, translated by Mary Cowden Clarke, 1–257. Cambridge Library Collection - Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Boyden, David D., and Ann M. Woodward. "Viola." Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 2 May. 2024. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000029438.

Brossard, Sébastien de. Dictionnaire de musique. Translated by James Grassineau. London: J. Wilcox, 1740

IMSLP, “Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 364/320d (Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus). Accessed May 2nd, 2024. https://imslp.org/wiki/Sinfonia_concertante_in_E-flat_major,_K.364/320d_(Mozart,_Wolfga ng_Amadeus)

Marissen, Michael. “Relationships between Scoring and Structure in the First Movement of Bach’s Sixth Brandenburg Concerto.” Music & Letters 71, no. 4 (1990): 494–504. http://www.jstor.org/stable/736819.

Pollens, Stewart (2009) "Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 14: No. 1, Article 6.

Stowell, Robin. The Early Violin and Viola : A Practical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ProQuest Ebook Central

Tarisio. “Stradivari’s Medici Quintet, Part 2 - Tarisio,” March 23, 2021. https://tarisio.com/cozio-archive/cozio-carteggio/stradivaris-medici-quintet-part-2/.

**Bonus joke because you made it this far!

Q: Why don’t violists get hemorrhoids?

A: Because all the a**holes play violin.

Robin Stowell, The Early Violin and Viola (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 28.

Sébastien de Brossard, Dictionnaire de musique, trans. James Grassineau (London: J. Wilcox 1740), 327.

Stowell, The Early Violin and Viola, 34; Boyden, Woodward, “Viola”.

Stewart Pollens. “Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin.” Performance Practice Review vol 14, no. 1 (2009): 3

Pollens, “Some Misconceptions”, 3

Pollens, “Some Misconceptions”, 38

my fave essay to read 🥹 p.s. i luv the illustrations!

so cool!!!